My grandfather left Poland as a teenager to work in the coal mines of Pennsylvania. He eventually married a Polish girl and made enough money to buy a farm near Pittsburgh, where they raised eight children. My mother, the hardest-working person I ever knew (she chose to work nights as a nurse so she could be home during the day for her four kids), often reminisced about her never-ending farm chores. If her father ever saw one of the kids sitting still, he would ask, “Are you sick?” And soon they would be heading to the barn or running several miles to pick up something at the store.

I thought a lot about that incredible Polish work ethic a thousand feet underneath the Krakow suburb of Wieliczka (vyeh-leech-kah) as I toured the ancient salt mine. The expression “back to the salt mines” refers to the Russian practice of punishing prisoners by sending them to Siberia to work in the salt mines.

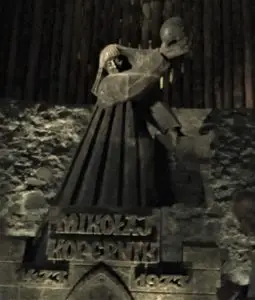

But it could also describe the lives of the dedicated men who turned the Wieliczka Salt Mine into a magical fairytale labyrinth of chambers and sculptures. The result is an underground journey into Polish history, with everyone from Copernicus to Pope John Paul II poised for selfies –salty versions of the stars at Madame Tussaud’s.

A rich history

The mine opened in the 13th century, when salt was as valuable as gold. For the next 500 years, the salt trade accounted for one-third of the income of the state of Poland. Salt was extracted from the mine up until 2007.

But while it might be interesting to see how salt is mined, that’s not why millions of tourists have been come here over the decades. The mine has intricate chambers chiseled entirely out of rock salt and saline lakes. All the sculptures, bas-reliefs, altarpieces, walls, floor tiles and chandeliers are made of salt. You can even lick the walls if you want – I declined but many kids seemed to enjoy it.

Originally the miners created chapels to provide the Catholic workforce with a way to celebrate Mass while underground. Shrines were chiseled near the miners’ workplaces and accident sites. But as the years went by, the simple chapels became more and more elaborate. Artisans spent much of their lives underground to create incredible works of beauty.

It took more than three decades for two brothers to carve away 20,000 tons of salt to form the Chapel of St. Kinga. It’s nearly forty feet high and covers 1,500 square feet, but perhaps my grandfather would have asked why the brothers didn’t work a bit faster. You can attend Mass or concerts in the chapel or rent it for weddings.

How Princess Kinga found salt in Poland

The St. Kinga Chapel illustrates the legend of Princess Kinga, a 13th-century Hungarian princess who became engaged to the Polish Prince of Kraków. She knew Poland had no salt mines, so she asked her father if she could bring a lump of salt as part of her dowry. The king agreed to let her take as much salt as she wanted from a Hungarian mine. To show her appreciation, the princess threw her engagement ring down one of the mine’s shafts.

She travelled to Poland for her wedding. One day, when she was visiting the neighboring town of Wieliczka, she saw shiny rocks that reminded her of the salt mine from her home in Hungary. The locals began digging, and when they found salt they also unearthed the ring Princess Kinga had thrown down the Hungarian mine. (yes, it miraculously traveled from Hungary to Poland.) Princess Kinga became the patron saint of salt miners.

The mine was one of the first twelve sites worldwide to be placed on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 1978. It was described as “the only mining site in the world that has operated without interruption since the Middle Ages to the present day.”

Touring the mine

The mine contains 186 miles of tunnels and 2,400 chambers. You won’t get lost since all visitors must be accompanied by a guide. If you’re visiting Krakow in the summer, the mine is the perfect place to go on a hot day because the temperature is always between 57 and 60 degrees. All the guidebooks advise bringing extra clothes but I never put on my jacket. All the walking will keep your body temperature up.

The ceilings of the chambers are high enough to keep you from feeling claustrophobic but at times, the crush of tourists made me somewhat anxious. The mine was quite crowded when I visited in August, but our guide gave us plenty of time to wander through the larger chambers. It is one of the top tourist attractions in Poland.

There are a total of 800 stairs leading down into the mines but the good news is that you take an elevator back to the surface. Still, there is about two miles of walking along the main Tourist Route, so wear good shoes. The floors aren’t slippery and it’s mostly level once you get down all those steps. Bringing water is a good idea as long as you don’t need to use the toilet too often. Facilities are available after roughly forty and ninety minutes of the tour, which typically lasts around two hours. It’s not easy to leave the tour early, since you would have to be guided to the elevator, so I wouldn’t advise it for anyone with health problems. Part of the route is accessible to people in wheelchairs, but you must contact the mine ahead of time.

Catholic visitors might be interested in the Pilgrim’s Route. A priest guides visitors through the mine’s chapels, focusing on statues of the saints and the bas-relief version of da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.” The priest can even celebrate Mass at the end of the tour.

While the Tourist Route is the most popular, many people, especially schoolchildren, don overalls and mining lamps for the Miners’ Route. You can actually dig for salt and even measure the concentration of methane in the air. I wonder if my grandfather, who came from a village near Krakow, could have ended up working here if he hadn’t emigrated. If he had, it certainly would have been healthier than working in a coal mine.

The microclimate is said to have many benefits due to the lack of pollution, allergens, bacteria and electromagnetic radiation. People with breathing problems can stay overnight at an underground sanatorium where the mine’s horses used to be stabled.

The Wieliczcka Salt Mine is just six miles from the center of Krakow and is easily accessible by public transportation. However, that means you’ll have to wait in line to get tickets and join a guided tour (tours in various languages are staggered), since visitors aren’t allowed to roam around by themselves. So if you are travelling during the busy season, you may wish to consider one of the many skip-the-line tours offered in Krakow, in which you are bussed from your hotel or a central meeting place to the mine. However, these tours will involve more walking because you will have to take a large group elevator back to the surface. That elevator comes out blocks away from where the mine’s entrance.

A place of magic

The Wieliczka Salt Mine is a fabulous contradiction—a workplace where thousands of men toiled for centuries to support their families and make the city of Krakow prosperous. But it’s also a magnificent underground cathedral that inspires awe, even for those who aren’t Catholic or particularly religious. As I wandered through the chambers, I wondered if my grandfather could have ever imagined that one of his several dozen grandchildren would return to his native land to see this treasure. The mine makes me proud to be Polish, even if I’ll never work as hard as my ancestors.

* * *

Read more Blue Hare

-

Chartres, Amiens, Reims: Three unforgettable day trips from Paris

-

When in Rome… selected day trips from the Eternal City women will enjoy

- Medieval to Regency: Day trips from London to explore England’s history