The United States is suffering its worst measles outbreak since the disease was declared eliminated in 2000. Most cases have been linked to international travel.

Measles is brought in by unvaccinated travelers (most of them Americans) who were infected in other countries. So says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

If you plan to travel this year—whether it’s domestic or international—you would be wise to check on your measles immunity well before you close the front door.

Recent measles outbreak

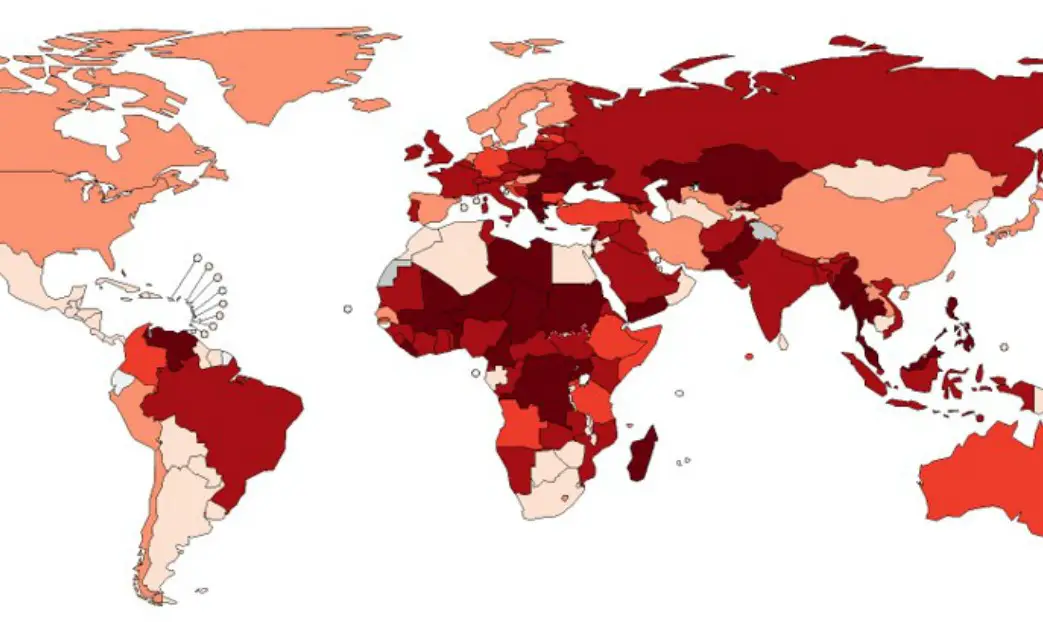

Measles has made a strong comeback not just in the United States, but in many other developed countries with high vaccination rates. Preliminary global data from the World Health Organization shows reported measles cases were up 300 percent in the first three months of 2019, compared to the same period in 2018.

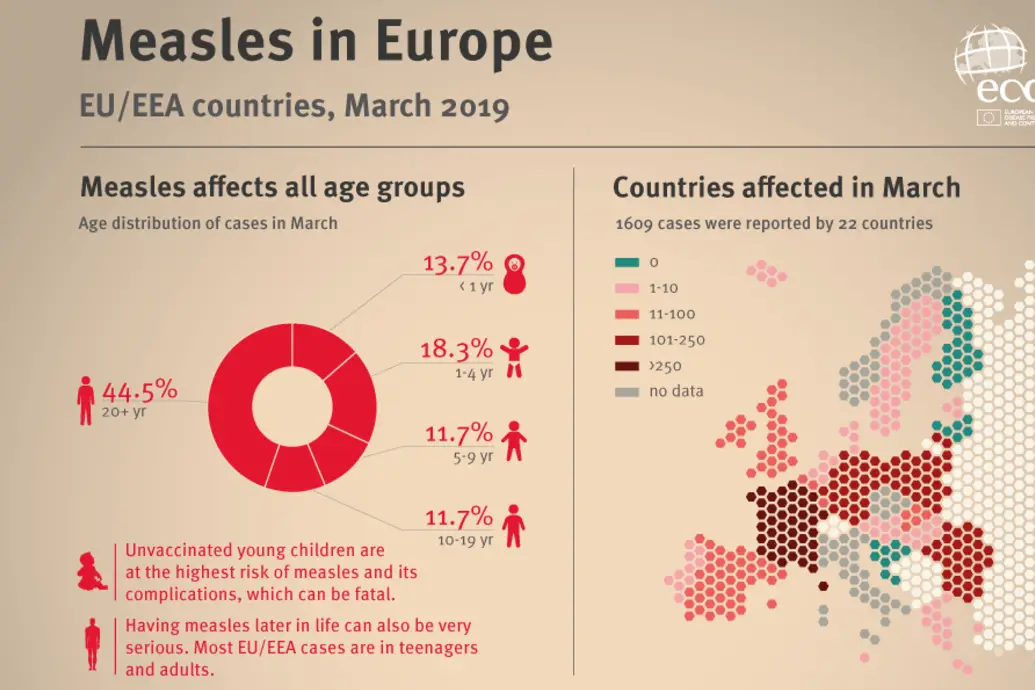

More than 100,000 measles cases and over 90 measles-related deaths have been reported in Europe since the beginning of 2018, according to the W.H.O. Japan is seeing its worst outbreak in more than a decade.

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease. It can cause death, deafness, and brain damage.

Measles lives in the nose and throat mucus of an infected person. It spreads through coughing and sneezing. And don’t think that you’re safe because no one has sneezed near you. The measles virus can live in the airspace where an infected person coughed or sneezed for up to two hours.

While measles can be serious for anyone, older adults and young children are more likely to suffer complications.

“There is no treatment and no cure for measles and no way to predict how bad a case of measles will be,” says CDC director Dr. Robert Redfield.

Measles can be prevented with a vaccine. It’s usually given as a combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) shot. Two doses are recommended. The first dose is approximately 93% effective at preventing measles; two shots are 97% effective. Although multiple studies have proven the vaccine is safe, parents reluctant to vaccinate their children to have contributed to the explosion of cases.

What baby boomers need to know

If you’re an adult without young children, you may not have thought much about the measles. Either you had it as a child or were vaccinated, so there’s no issue, right? Not so fast. The CDC recommends that adults who can’t prove their immunity be vaccinated, especially if they are planning to travel abroad.

It’s probably not easy for baby boomers to remember whether they had measles or were vaccinated as a child. Finding the documentation is even tougher. It turns out many younger baby boomers may be more at risk than they suspect.

If you don’t know your measles status, it’s best to talk to your doctor about testing and vaccination.

Understanding how your birthday matches up with the fight against measles can give you a better idea of whether you need to be concerned. Keep in mind that, while most children are vaccinated between 12 and 15 months of age, your vaccination may have been later.

ADVICE FROM THE CDC

Adults traveling overseas should have two doses of the measles (MMR) vaccine separated by at least 28 days at least two weeks before their trip, unless they have evidence of immunity.

While most American adults are protected against measles, everyone who can’t prove immunity is advised to get at least one dose of the vaccine.

If your birthday comes before 1957, you’re covered

When it comes to measles protection, being older is actually good news. If you were born before 1957, you are considered immune to measles, according to the CDC. That’s because measles was so widespread everyone was exposed. The measles vaccine was introduced in the United States in 1963. Before this time, at least three million people got measles each year, 48,000 were hospitalized, and four to five hundred died.

If you had just one bout of measles, you’re immune for life. So, if you’re now 63 or older, you don’t need to worry about catching measles or bringing the disease back to your grandchildren. You can cross measles prevention off your travel checklist.

If you were born between 1957 to 1963, you may have had measles, but can’t prove it

In the decade before 1963, when measles immunization began, nearly all children got the measles by the time they were 15. Many even attended “measles parties,” as it was widely believed that infected children would build up immunity to the virus. Once someone has the measles they cannot catch it again.

But if you were born from 1957 onwards, you are not considered to have evidence of immunity. The CDC’s acceptable evidence of immunity includes at least one of the following:

- Birth before 1957

- Written documentation of adequate vaccination

- Laboratory evidence of immunity

- Laboratory confirmation of measles

So, a memory of an itchy rash isn’t enough to prove immunity for a 60-year-old. Perhaps you had chickenpox instead. Most of us don’t have access to our childhood medical records. And if you had a mild case of the measles, you might not have even seen a doctor.

If you were born between 1963 and 1976, you were probably vaccinated, but you may not be immune

If you grew up in the sixties, you may remember getting a measles shot. Unfortunately you may have received the wrong one.

Two types of vaccines were licensed in 1963. One was a weakened form of the live virus. It was highly effective but had side effects. The other contained an inactivated (dead) form of the virus. It was later found to be ineffective. The CDC estimates that between 600,000 to 900,000 Americans received the ineffective vaccine. The rub is that people typically have no idea which vaccine they were given.

In 1968, an improved live vaccine with fewer side effects was introduced. By 1976, the Edmonston-Enders vaccine was the only one used in the United States. It is still used today. But another, less effective, version of the live vaccine (Edmonston B strain) was given from 1963 to 1975. The CDC reports nearly 19 million doses were given. They may have been less effective because patients also received immunoglobulin.

If you were vaccinated prior to 1976, you can’t be positive you are immune from measles. You need to be able to document you received the Edmonston-Enders vaccine.

Also, those vaccinated before 1989 probably only received one dose. Two doses are now recommended. One dose of the modern vaccine is 93 percent effective. This means those vaccinated between 1976 and 1989 shouldn’t have to worry much. Still, they might want to consider getting a second dose.

Is there a way to find out if I have immunity?

You can get a blood test to determine whether you are immune to the measles. But, this will typically take two doctor’s visits and cost more than the vaccination itself. It’s probably easier to just get immunized. The CDC advises this is safe even if you’ve already had the measles or have been vaccinated.

“In general, the documentation of vaccination trumps any immunological test,” says CDC Vaccine Director Dr. Nancy Messonnier.

Who should get vaccinated?

“Most adults are protected against measles, including people who were born before the measles vaccine was recommended,” says Messonnier.

However, the CDC recommends at least one dose of the MMR vaccine for any adult born after 1956 who cannot show evidence of immunity.

Measles and travel

The CDC is most concerned about Americans who travel overseas. If you are planning to leave the country, the CDC recommends two doses of MMR vaccine. These need to be given at least 28 days apart, unless you have evidence of immunity.

“People traveling internationally should try to be fully vaccinated at least two weeks before traveling,” says CDC director Dr. Robert Redfield. “But even if your trip is less than two weeks away you should still get a dose before you depart.”

The CDC also recommends two doses for other high-risk groups such as college students and healthcare personnel.

Which countries are the most dangerous?

The World Health Organization reports all regions of the world are seeing a sustained rise in measles cases. Current outbreaks include the Philippines, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Madagascar, Thailand and Ukraine. WHO also reports spikes in countries with high overall vaccination coverage. Countries like Israel, Thailand, and Tunisia.

The CDC currently has measles travel notices (Watch Level 1- Practice Usual Precautions) for Brazil, Israel, Japan, the Philippines, and Ukraine. If you are going to these countries, it is critical to follow the CDC guidelines of two MMR shots for all foreign travel.

Visit the CDC Travel Health Notice page to check your travel destination for the latest information.

A 2019 study published in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases found the countries with the greatest measles risk for American travelers are India, China, Mexico, Japan, Ukraine, Philippines, and Thailand.

Europe is also seeing a surge in measles cases. The highest numbers are in Romania, France, Poland, Lithuania, and Italy (as of March 2019). Large outbreaks with fatalities are ongoing in countries that had previously eliminated or interrupted endemic transmission.

Do I need to provide evidence of measles immunity when I travel?

Right now, no country is asking for evidence of immunity or proof that you were vaccinated before you cross its borders. And the United States doesn’t require evidence before you return.

However, with no sign yet that measles outbreaks are waning, it is possible you may find yourself subject to a quarantine. Just this month, passengers on a cruise ship were not permitted to disembark at St. Lucia due to a measles outbreak. In another instance, hundreds were quarantined in Los Angeles at two universities due to measles exposure. Faculty and students had to stay home unless they could provide proof of immunity.

So, if you do get the measles vaccine before you travel or have medical records showing your immunity, bring that documentation with you.

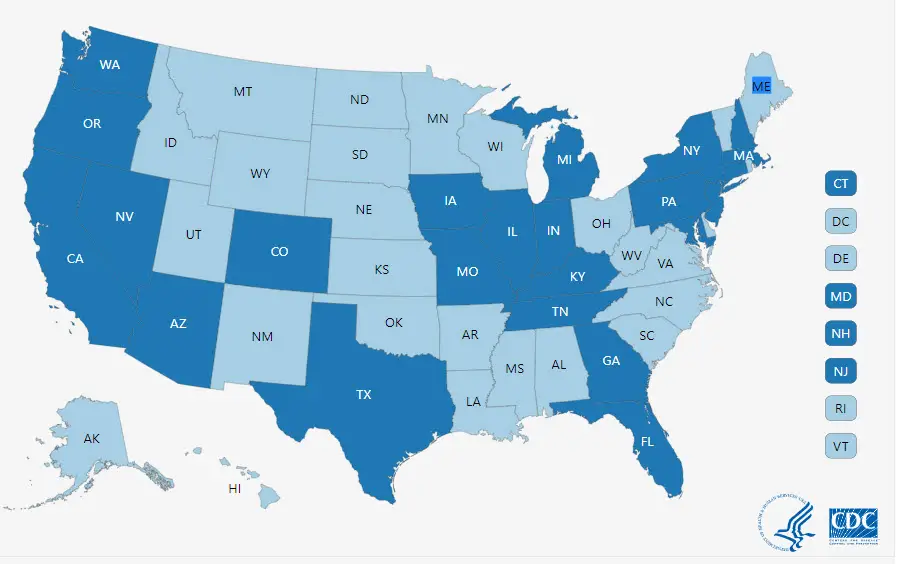

The CDC says 23 states have reported measles cases in 2019. The worst outbreaks occurred in Orthodox Jewish communities in and around New York City (Brooklyn and Rockland County) and northern New Jersey. Parts of Michigan, Washington State, and California have also reported outbreaks. An outbreak is defined as three or more cases in a cluster.

A 2019 study published in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases predicts the areas surrounding Chicago, Los Angeles, and Miami are at the highest risk for future outbreaks. The authors, who analyzed factors such as international air travel and low vaccination rates, say these areas should be kept under close surveillance.

Do I need to get vaccinated if I’m traveling in the United States?

The CDC is focusing on overseas travelers, but it also recommends one dose of the MMR vaccine for all American adults born after 1956 who cannot show evidence of immunity. As described earlier, people vaccinated before 1976 might have received a less effective shot.

While it’s unlikely many older adults will rush to see their doctor, you should consider the vaccine if you are going somewhere with an outbreak. As you can see, this includes a lot of favorite vacation destinations. If in doubt, get vaccinated.

Measles is so contagious that about 90 percent of people who are exposed will catch the virus if they are not immunized. And even with modern medical care, the disease kills one or two out of every 1,000 victims, according to the CDC.

So, if you’re not sure if you had the measles or were vaccinated properly, review the CDC’s recommendations and talk to your doctor.

The CDC strongly advises vaccination for adults without proof of immunity before overseas travel to prevent measles from being imported. Even though most older adults probably have at least some protection against catching the disease, a faulty memory could turn you into patient zero for a measles outbreak.

Want to know more? Here’s a guide to measles symptoms

Measles signs and symptoms appear around 10 to 14 days after exposure to the virus. The Mayo Clinic lists typical symptoms:

- Fever

- Dry cough

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis)

- Tiny white spots with bluish-white centers on a red background found inside the mouth on the inner lining of the cheek — also called Koplik’s spots

- A skin rash made up of large, flat blotches that often flow into one another

The infection occurs in stages over a period of two to three weeks.

- Infection and incubation. For the first 10 to 14 days after you’re infected, the measles virus incubates. You won’t have any signs or symptoms during this time.

- Generalized symptoms. Mild to moderate fever, often accompanied by a persistent cough, runny nose, inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis) and sore throat. These can last for two or three days.

- Acute illness and rash. You’re a good two weeks into the infection when a rash appears. The rash consists of small red spots. Some will be slightly raised. Spots and bumps in tight clusters give the skin a splotchy red appearance. The face breaks out first.

- Over the next few days, the rash spreads down the arms and trunk. Then it spreads over the thighs, lower legs, and feet. At the same time, the fever rises sharply. It is often as high as 104 to 105.8 F (40 to 41 C). The measles rash gradually recedes, fading first from the face and last from the thighs and feet.

- Communicable period. A person with measles can spread the virus to others for about eight days. This starts four days before the rash appears and ends after the rash has been visible for four days.

Source: mayoclinic.org

Header image: travelvox.com.au

* * *

You may also like

- Think you need less sleep as you age? Think again.

- Your doctor wants you–to get these important vaccinations when you turn 65

- Red in the face: We look at rosacea and treatments that work

Go to the Blue Hare home page for more articles for fabulous women.