Now that we are in our sixties, our immune systems aren’t what they used to be. We (and it) need outside help in the form of vaccinations to ward off some serious diseases. This isn’t scare mongering. An estimated 80,000 Americans died of flu and its complications last winter—the disease’s highest death toll in at least four decades. And flu isn’t the only awful disease that is prevalent in our age group: we should also be afraid of shingles and pneumococcal pneumonia, as well as others like Hepatitis C.

Here is a quick rundown of what you need to know about the three vaccinations you should get once you’ve hit 65. If you read only one article in this magazine this week, let it be this one.

The Flu Vaccine

A quick rundown

Flu vaccines protect against A and B influenza strains. A-strains of the flu can be transmitted between humans and animals, and are generally responsible for large flu epidemics. B-strains are found only in humans, usually provoke less severe reactions, and do not cause pandemics.

There are hundreds of A-strains that are mutating constantly and hard to predict, while there are only two B-strains. The trivalent vaccine protects against three different flu viruses: the two most common A strains (H1N1 and H3N2) and one B strain (either Massachusetts or Brisbane), whichever is predicted to affect the public most strongly in a given year.

Recent research has now given us the quadrivalent vaccine. This form offers the same benefits as the trivalent vaccine, with the added bonus of covering both B-strains, so four strains in total. Both B-strains have been detected within the United States in the past 10 years.

Overall, both types protect against the flu. For seniors (65+) the general recommendation is one of the two formulas specifically geared to adults age 65-plus: either the high-dose or the adjuvanted vaccine, but you should discuss this with your doctor. The quadrivalent vaccine can cost more than the trivalent form and Medicare may not pay for the total cost. Be sure to check with your insurance provider to determine your coverage.

See our in-depth article about the flu and how it affects baby boomers at the height of the epidemic in the February edition of this magazine, in an article called “The 2018 flu: What baby boomers need to know”.

When should you get the vaccine?

Flu season generally starts in late fall and peaks in January/February, although it can continue into March. It’s recommended to get the vaccine by the end of October, or as soon as possible into the flu season if you’ve been lax. Influenza activity might not occur in certain communities until February or March.

How is it administered?

The flu shot is a single dose injected with a needle into the upper arm on your least dominant side.

Take this action

The best time to get the flu shot is right now. Make a doctor’s appointment as soon as you read this.

Pneumococcal Disease

A quick rundown

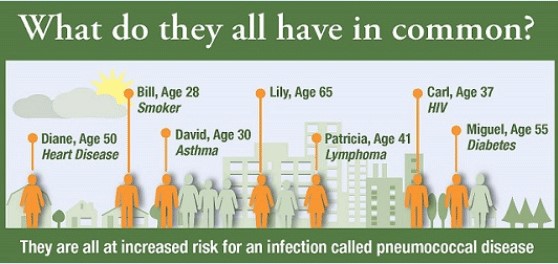

Pneumococcal disease is an infection caused by a type of bacteria called streptococcus pneumoniae, which can cause pneumonia. Less known, though, is that the bacteria can also invade the bloodstream, causing bacteremia (presence of bacteria in the bloodstream), and can also invade the tissues and fluids surrounding the brain and spinal cord, causing meningitis. Pneumococcal disease can also cause middle ear infection and sinus infections.

Pneumococcal disease kills thousands of people in the U.S. each year, most of them age 65 years or older. Only 56 percent of non-institutionalized American adults 65 years of age or older and fewer than 20 percent of adults in other high-risk groups who are recommended for the pneumococcal vaccine have received it.

What is important to know is that there are two types of pneumococcal vaccines:

- PCV13 (pneumococcal conjugate vaccine), which protects against 13 strains of pneumococcal bacteria, including pneumonia.

- PPSV23 (pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine), which protects against 23 strains of pneumococcal bacteria, but not pneumonia.

The CDC recommends both pneumococcal vaccines for all adults 65 years or older.

When should you get the vaccine?

Pneumococcal vaccine can be given at any time during the year and can be given at the same time as an influenza vaccine. You should receive a dose of PCV13 first, followed by a dose of PPSV23, at least one year later.

How is it administered?

The pneumococcal vaccine is a single dose injected with a needle into the upper arm on your least dominant side.

Take this action

Because the pneumococcal vaccine is administered in two doses and because the timing is so important, it is crucial that you discuss this vaccine with your doctor. In addition, if you have a compromised immune system or if you have had previous doses of a pneumococcal vaccine, the recommended timing and dosage may not apply to you. Call your doctor!

Shingles (herpes zoster)

A quick rundown

Shingles is essentially a reactivation of chickenpox. The “pox” in the name refers to its blistering rash. For much of human history it was thought to be similar to smallpox (another illness with a blistering rash). However, the two infections are entirely unrelated. Why it was called “chicken”-pox is not entirely clear since the disease has nothing to do with chickens. The scientific name of chicken pox is varicella.

Varicella is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Varicella can be fatal, but most people survive the initial infection. However, even though the rash eventually disappears, the virus is never entirely cleared from the body. It remains dormant in the dorsal root ganglia, a cluster of nerve cells that run parallel to the spine. Your immune system normally keeps the virus in check. But as we age, our immunity wanes. By age 55, 30-40% of people have lost the specific immunity they had to the varicella-zoster virus and the virus can re-awaken.

This second VZV infection is not like the first. Whereas varicella (chickenpox) is a diffuse rash that spreads across the body, this second infection has a more limited spread. When the virus escapes from the dorsal root ganglion along the spine, it follows the path of a single nerve group. Starting from the back it arcs around the thorax toward the front on only one side of the body. The medical term for shingles is herpes zoster.

Shingles is not generally a fatal condition. However, if it spreads along a nerve leading to the eye it can cause blindness. Its main medical symptom is pain. The pain associated with shingles can be intense and debilitating. While the pain usually subsides after 3-4 weeks, in some people it can turn into a chronic pain syndrome called post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), which is often so defeating that it can lead to depression and loss of any quality of life. In fact, the reason that shingles can be so serious for people over 65 is that if it strikes when a person is dealing with another issue (such as diabetes, chemotherapy, dialysis, etc) the pain can lead to a loss of will to live.

The old vaccine–Zostavax—contained a live virus that was modified to make it weaker, less able to cause an infection, and easier for the immune system to kill. It was about 64% effective in people between the ages 60-69, but its effectiveness declined with increasing age, and it lost its effectiveness over time.

The good news for the over-60 crowd is that in October 2017, the FDA approved a new shingles vaccine, called Shingrix. Shingrix is an inactivated recombinant vaccine (different from live virus in that it contains killed virus), so can be used in people with a compromised immune system. It is measurably better than Zostavax. Two doses of Shingrix is more than 90% effective at preventing shingles and PHN.

When should you get the vaccine?

You can get the vaccine at any time of the year. It is recommended that people who got Zostavax get re-vaccinated with the new Shingrix vaccine. Shingles can strike twice, although it is rare, so those who have had a previous episode should also get vaccinated. Remember that you need to be vaccinated two to six months after the first vaccine. If you let that time frame lapse, your first shot will not be enough to prevent an attack.

How is it administered?

The zoster vaccine is a single dose injected with a needle into the upper arm on your least dominant side. Repeated two to six months later. For cost/coverage issues your doctor may advise that you receive your vaccine at a local pharmacy.

Take this action

See your doctor about getting the Shingrix shot. Ask your doctor’s office to make the appointment for your second shot when you have your first. Timing is key with the Shingrix shot. Do not miss your second shot or your first one is useless.

A word about cost

The Shingrix vaccine is expensive—about $280 for the two shots—and is not covered by Medicare Part A or Part B. Medicare Part D prescription drug plans will cover the shingles vaccine but it is subject to a copay, which can be hefty. Talk to your doctor and pharmacist about your options.

Availability

Because its effectiveness has been highly touted since its FDA approval, there has been a shortage of supplies of Shingrix in the United States. Production has been accelerated but you may still have to put your name on a waiting list, so it is important to see your doctor now to get the ball rolling.

* * *

About the header photo: Health service company Cigna brought together some of TV’s top docs to encourage Americans to get an annual checkup. The ad campaign debuted in 2016.

You may also like

- The 2018 flu: What baby boomers need to know

- Drink black tea. More than your taste buds will thank you.

- Thirsty? Easy ways to stay hydrated if you don’t like water.

…and more on the BLUE HARE home page.